When we open our browser and type in a URL or click a link, we see a rendered web page spread across our screen. It’s fonts, graphic images and words construct an image with it’s own identity.

But at a physical level, it can take on a whole new meaning. At one level, we hear it all just a series of ‘1’ and ‘0’ binary digits stored in computer memory. Go deeper and you’re into the mysterious quantum world of electronic semiconductors. These things are hard to grasp and visualise of course.

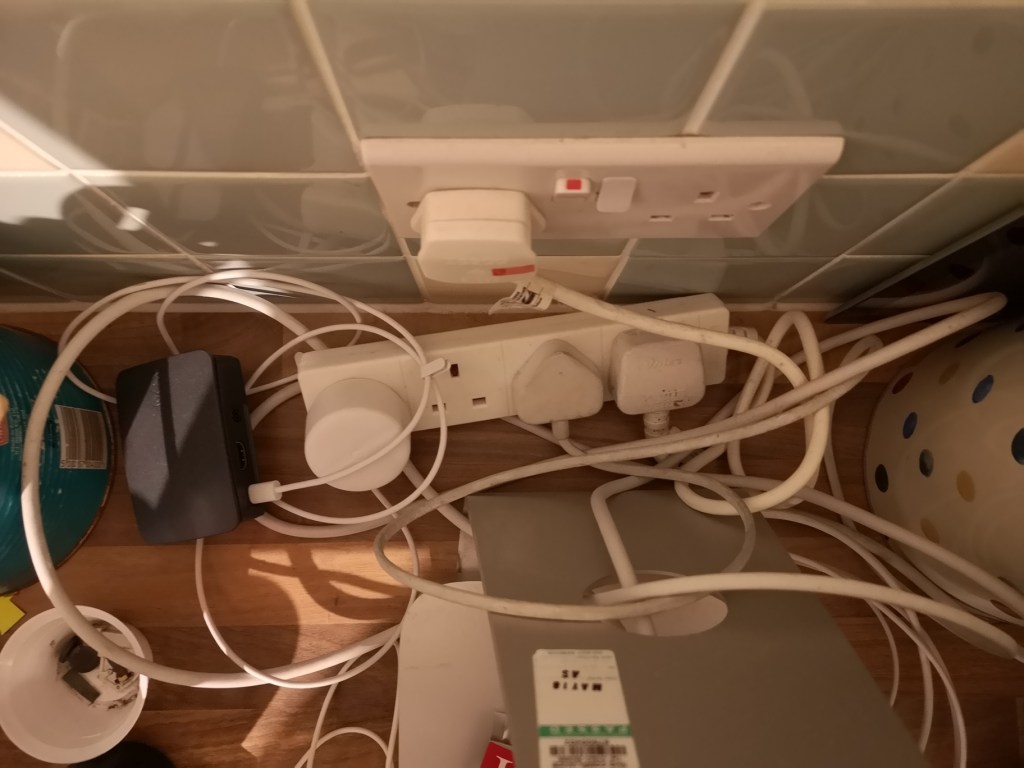

Much more tangible is the computer itself. When you open the webpage, somewhere (ok, my kitchen as it turns out) a small computer wakes up and begins a flurry of electronic activity, serving up the data that renders this very page.

The computer (aka Server) is a Raspberry Pi. A cheap low power computer that is approximately the size of a credit card. It is switched on 24/7, listening for incoming connections from the Internet, from anywhere in the world.

The actual computer is even smaller. It is strange how something so small produces a rendered page so quickly. Every time you access a new page, this tiny chip fetches data from its memory, generates a webpage that your device can display and sends it back to you over the Internet.

When it comes to it, the web page is only a tiny fraction of the data used by the computer. In volume terms, it’s a tiny dot within the 165 cubic millimetre volume of the whole storage device.

This web site is very much a proof of concept, but it’s pleasing what can be done with a £30 computer hooked up to home broadband and tucked out of sight in a kitchen. The wiring does need to be hidden from my wife however 🙂

Going forwards, we may need to move this webpage to a “proper” hosting solution where the computers are backed up, maintained in a controlled climate, and where there is no risk that someone doing the washing-up will pour soapy water over the whole facility.

Nick